A Fragrant Frontier in Trademark Law…

On 21 November 2025, the Indian Trade Marks Registry made history by accepting the country’s first olfactory (smell) trademark. The mark in question: a rose-like floral fragrance infused into tyres by Sumitomo Rubber Industries.

Why This Matters

This isn’t just a quirky IP footnote. It could be the opening of a whole new dimension in Indian trademark law. Traditional trademarks are usually words, logos, or shapes. But non-conventional marks like scent, sound, or colour challenge the legal system because they’re intangible.

Here, the Registry evaluated the application under two critical statutory criteria:

- Graphical Representation (Trade Marks Act, 1999, Section 2(1)(zb)), and

- Distinctiveness.

Getting over these hurdles is not straightforward for smells.

The Legal Hurdles & How Sumitomo Overcame Them

1. Graphical Representation

A major roadblock for scent marks. Because smells can’t be drawn like a logo, the Registry questioned how to “represent” them graphically.

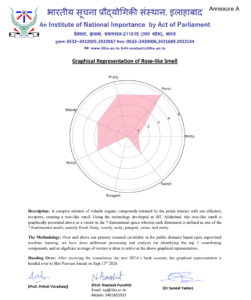

- Sumitomo submitted a scientific model created by researchers from IIIT Allahabad.

- The model maps the “rose-like smell” in a seven-dimensional space, breaking it down into basic smell families: floral, fruity, woody, nutty, pungent, sweet, minty.

- The Registry found this representation to satisfy legal standards: “clear, precise, self-contained, intelligible, objective and durable.”

This is a fascinating legal innovation: using a scientific vector model to represent something as subjective as smell.

2. Distinctiveness

- The scent is arbitrary relative to tyres (roses and rubber don’t naturally go together), which helps its case.

- The Registry reasoned that because tyre rubber typically smells like rubber, a floral scent would stand out. That novelty helps consumers associate the smell with Sumitomo specifically, not just any tyre.

The Role of Amicus Curiae

Because this was uncharted territory, the Registry appointed Pravin Anand, a senior IP practitioner, as amicus curiae to assist.

He submitted detailed scientific and comparative analyses supporting Sumitomo’s arguments, helping bridge the gap between legal standards and sensory science.

His key point: Indian law doesn’t explicitly forbid scent marks. And because the Trade Marks Act has a broad definition of “mark,” such non-conventional marks are, in principle, possible — if you can meet the representation and distinctiveness rules.

Broader Legal & Policy Implications

- Precedent for Non-Traditional Marks

- This could be a precedent for other companies seeking sensory branding protection in India.

- It signals that the Registry is open to non-conventional marks, not just the usual text or logo.

- Graphical Representation Standards

- The adoption of a scientific, vector-based model may influence how future smell-mark applications are structured.

- It also raises the bar: such graphical models need to be rigorous, objective, and durable.

- Regulatory Evolution

- While the Trade Marks Act doesn’t explicitly discuss smells, the Registry’s decision suggests a flexible interpretation.

- This could invite policy reform, as discussions grow around formalising smell marks in Indian trademark guidelines.

- The “functionality doctrine” will likely be a recurring debate — if a scent has a useful or functional purpose, should it be registrable?

Risks & Challenges Ahead

- Enforcement: Even if the smell is registered, policing infringement could be tricky. How do you prove someone is copying a smell?

- Consumer Perception: Will consumers actually associate a rose-like scent with tyres and see it as a brand identifier?

- Cost & Complexity: Building a scientific representation model, like Sumitomo did, is expensive. Not all businesses can afford that.

Conclusion

Sumitomo’s successful smell-mark application is a landmark moment in Indian IP law. It opens up new creative and commercial possibilities, especially for brands that want to use scent as part of their identity. At the same time, it forces legal systems to expand in how they define, represent, and enforce trademarks that are not purely visual or verbal.

For law students, academics, and IP practitioners, this case is now one to watch closely. It’s not just about tyres and roses, it’s about how the senses themselves might become protectable under law.

What are your thoughts on this?

1 Comment

Pingback: The Sweet Smell of Precedent: Unpacking India’s First Olfactory Trademark – The IP Press