Introduction

For quite a long time, India has been dealing with the issue of discrimination based on gender, religion and especially caste. It is said that caste discrimination is not a question of presence or absence, but of form. In rural spaces, it speaks loudly and openly, and in urban India, it becomes more subtle and indirect. The issue becomes more problematic when such discrimination penetrates institutions where youth are educated to unlearn such evils and dismantle the hierarchy. The contradiction becomes stark.

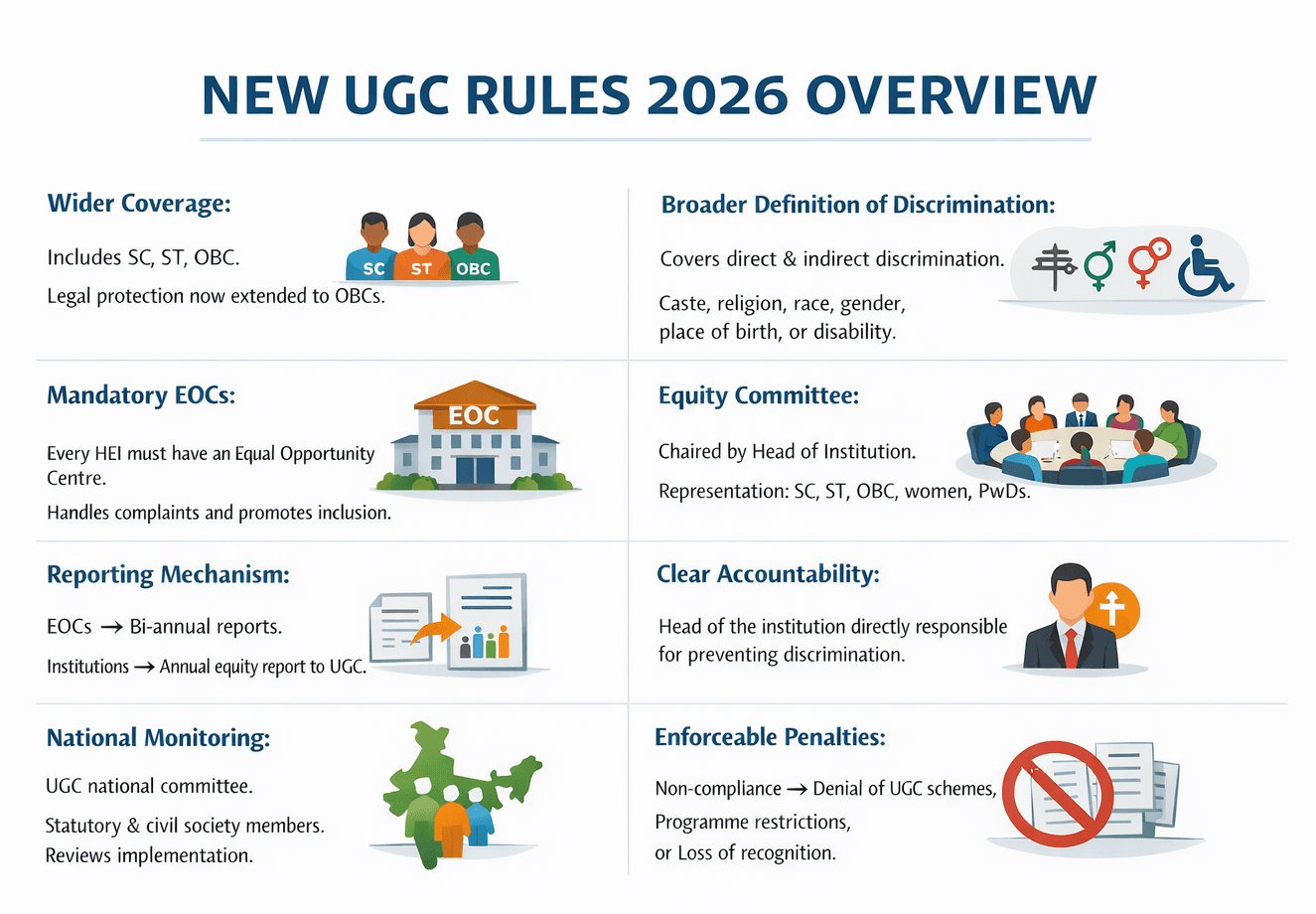

In January 2026, the University Grants Commission (UGC) notified the Promotion of Equity in Higher Education Institutions Regulations, replacing the 2012 framework with a more robust regulatory regime. This article traces that evolution, examines the ground reality of discrimination in universities, evaluates the strengths and weaknesses of the new regulation, and concludes with a personal opinion.

The 2012 Regulations

The 2012 Promotion of Equity in Higher Educational Institutions Regulations mandated the establishment of Equal Opportunity Cells (EOCs) in universities and colleges to address cases of discrimination on grounds including caste, religion, gender, disability, and ethnicity. In practice, the protection mechanisms often highlighted SC and SC as core beneficiaries. Institutions were required to appoint an anti-discrimination officer, set up an equal opportunity cell, and decide on a discrimination complaint within 60 days.

The framework failed to define what constitutes a false complaint, what the penalties were for malicious allegations and did not mandate any external verification, making the implementation deeply uneven.

As per data submitted by the UGC in the Supreme Court in 2025, out of 1314 complaints received under the 2012 regulations, 1276 were resolved. The number looks quite impressive, but on the other hand, there was no clarification on what resolution actually means or what the outcomes of the cases are, creating additional informational gaps and opacity.

For these reasons, the regulations were criticised as advisory rather than enforceable rules. Many EOCs remained dormant or lacked clarity on procedures, leading to scepticism about their actual impact.

Ground Reality- The Stark Rise in the Number of Complaints

The data presented by the UGC to the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Education points to the unpleasant reality of escalating complaints of caste-based discrimination over the past five years.

Complaints rose from 173 in 2019–20 to 378 in 2023–24 across 704 universities and 1,553 colleges. The total number of caste discrimination complaints received between 2019 and 2024 was 1,160, of which 1,052 were reportedly “resolved,” implying a disposal rate of about 90.7 per cent. However, the number of pending cases increased from 18 to 108 over the same period.

We can draw two possible interpretations from this data. Firstly, there is an increase in discriminatory behaviour on campus, and secondly, there is greater awareness among students and faculty about reporting mechanisms.

The 2025 Draft Regulations

The 2025 draft (notified as the 2026 Regulations) represents a significant shift. Instead of mere guidelines on paper, it aims to create a legally mandated regulatory scheme aimed at fostering equity and anti-discrimination mechanisms. Core elements are:

- Mandatory Equal Opportunity Centres (EOCs) in all HEIs.

- Institutional Equity Committees, chaired by the head of the institution, with representation from SC, ST, OBC, women, and persons with disability.

- Time-bound grievance redressal, with inquiries to be initiated within 24 hours and reports submitted in 15 working days.

- 24×7 equity helplines and online complaint portals.

- Equity squads and ambassadors to monitor campus spaces.

- Penalties for institutional non-compliance, including debarment from UGC grants, bans on online or distance programmes, and removal from UGC’s approved list.

These provisions are different from the earlier framework as they impose clear institutional obligations and enforcement measures.

The Strengths of The New Model

One of the major critiques of the 2012 rules was non availability of time-bound action. The new rules hit the spot and mandate swift and transparent action on the complaints. Also, the move to include faculty and non-teaching staff acknowledges the fact that discrimination is not limited to student-student interactions, but also the institution as a whole. Online portals and helplines make the forum more accessible and reduce dependence on ad-hoc channels, thus diffusing the old bureaucratic layers.

For these reasons, the draft represents a notable endorsement of an anti-discriminatory environment and empowers the beneficiaries to raise their voice.

Loopholes and Areas of Concern

The new regulations have a non-neutral definition of caste-based discrimination. It defines caste-based discrimination only in terms of harm to SC, ST, and OBC communities, whereby the non-reserved category is excluded from the protection. There are no clear penalties for false or malicious complaints, raising concerns that the rules can be weaponised in personal conflicts and academic rivalries. Also, the continued presence of equity squads and monitoring will affect classroom discussions, debates or continuous research topics, whereby there is a possibility of misinterpretation and misuse.

Further, the regulations vest the chairmanship of the committee in the Head of the Institution, typically the Vice-Chancellor or Principal. In the Indian higher education system, these positions are overwhelmingly occupied by people from the general category, which has been seen in institutional leadership data across central and state universities. This structure can create an apprehension of bias, even if no bias is overtly exercised.

Also, the regulations mandate representation of women and members of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes on the committee, but such representation is by nomination and not by election. This raises serious concerns about independence and effective participation of marginalised stakeholders. Their presence becomes merely tokenistic just for the sake of formality.

Final Thoughts

In his Constituent Assembly speeches, Dr B.R. Ambedkar reminded the nation that political equality can be sustained only by social and economic equality. Seen through that lens, the present framework risks turning equality into a matter of individual complaints rather than collective justice. The rules cannot just focus on isolated issues without questioning who holds the power.

The pursuit of equity in higher education is necessary and non-negotiable. Yet, the legitimacy of any framework lies not merely in its intention but in its design. By focusing on complaint-driven redressal without adequately redistributing power or representation, the framework ends up offering equality on paper. The deeper social and economic hierarchies that Ambedkar warned us about remain largely unchanged, quietly impacting outcomes even as the process claims to be fair.